Digital transformation is on the agenda of nearly every company. Travel and hospitality companies have adapted to decades of disruption from online travel businesses. Financial services organisations have embraced big data and machine learning in order to expand the scope of their services and now contend with a range of fintech players. The music industry suffered challenges on various fronts — from illegal downloading and sharing to streaming — before making its adjustment. Meanwhile, the traditional insurance business model has endured intact despite disruptive technologies in every other sector. The question is, for how long?

Industry experts know the insurance sector needs to reinvent itself with major revisions needed in operating models, processes, propositions and customer relationships. However, it is a colossal task. Digital transformation is possible, but not without a substantial cultural shift — at both company and industry level.

There is no shortage of ideas around the industry for accelerating client-facing innovation, but these remain difficult to implement properly. In the near term, clear opportunities for unlocking value lie with end-to-end operational transformation.

We spoke with senior executives from insurance companies across Europe to find

out what is at stake in their move toward digital and to understand the

implications for talent. The challenges they described fall into five categories:

data management and analytics; technology debt; the role of the board; cultural

transformation; and the talent bottleneck. Nobody has to tell these leaders that

change is upon them. They are dealing with it every day.

1. Too much data

Insurance companies are already good at pooling and analysing data for opportunities and customer information, linking it to risk assessment, billing, claims handling and pricing. However, the types of data available now come from a universe of information that is different in category and volume (telematics is just one example, with user-based insurance (UBI) expected to reach 26 per cent market share in the US and 38 per cent in the UK by 2020). The set of available data points is getting larger, with a continuous flow of information in real-time, often from external sources. Coping with this kind of digital information requires a novel approach, far beyond the boundaries of traditional actuarial science.

One solution to coping with an abundance of data is to address it in iterations. Companies can create a repository of internal data, clean it up, test ways it can provide a service the customer wants, then bring it to scale, moving incrementally. It may also be appropriate to segment a part of the business in which to capture business value on real-time information and create customer interfaces, rather than taking on the whole of the enterprise in one gulp. Ultimately, however, successful innovation in the digital arena will require breaking down traditional silos in order to build a new level of trust and collaboration across the whole organisation.

Aviva’s group chief operations and IT officer, Nick Amin, began changing the way the company did business by choosing a location to focus upon in which they had a critical mass. “That was the UK,” he says, “we really wanted to win there. We took level 39 at Canary Wharf and held our first hackathon, which ran through the weekend. We replicated this quickly all over the world and now have an established community focused on developing insurance technology ideas.”

2. Technology debt

Insurance was one of the early adopters of information technology and many insurance companies’ systems originate from pre-internet days. Over time, added capabilities have been tacked on in order to improve performance. The resulting infrastructures are complex and idiosyncratic. The older, bespoke technology cannot cope with new information brought on by data points derived from recent technology embedded in the “internet of things.” Idiosyncratic and lacking in many ways, legacy technology comes with a mass of “technology debt.” That is, workaround solutions that now cost the company a lot to service. These systems offer just enough sophistication to make them a barrier to the adoption of newer, far more flexible technology, free of dependencies and broken processes.

“The moment you add in a digital disruptor, you change parameters,” says Elisabetta Pizzini, business development director in Italy for the The Floow, a company that works with motor insurers and auto organisations, providing data collection, storage, management and interpretation. “For example, it becomes difficult for the insurance company that has always been able to price the risk, taking learning from past experience and projecting into the future, to accept a different parameter that has not been proven to be correct.”

The moment you add in a digital disruptor, you change parameters.

Elisabetta Pizzini,

Business development director, Italy, The Floow

An older system may also have business units or departments on platforms that don’t fit together. Fragmentation can also occur as a result of acquisitions, merging departments and years of divergence in a company’s IT policy. It is difficult to justify upgrading or re-platforming a system when it is still working, as the ROI may not be apparent during the tenure of the existing management team. But the costs of not doing so scale up with the size of the organisation, as does the time required to address the issue. Because technology debt is difficult to quantify and is not a traditional expense item, it does not show on a company’s P&L.

The solution may be to find ways of incorporating existing data with new types of data (including large-volume and unstructured data), and using some of the tools now available to migrate from existing databases to new platforms. Insurance companies need to be aware of new sources of external data to help them make decisions. The challenge is to build a strategy with flexibility to cope with an increasingly digital world. New analytics tools with insurance applications are appearing all the time, such as Hortonworks’ Hadoop, a data platform used by Progressive and others for their UBI products. It may be worth adopting Aviva’s idea of a “Disruptive Innovations Programme” or taking the advice of Pietro Guglielmi, chief digital officer at AXA Italy, who recommends looking beyond the insurance world to external fintech suppliers in order to provide solutions.

3. The importance of board support

Companies from all sectors are grappling with the question of how to educate the board on the opportunities and threats brought by digital. One solution is to recruit a director with a digital background who can support and challenge the executive team, as well as act as an interpreter between the executive and the rest of the board on digital matters. Among the top twenty European insurance companies, only ten have a non-executive director with digital expertise. The boards of three companies have no non-executive directors with digital, customer relationship or marketing operations experience.

There are exceptions. Claudio Dozio, HR director for EMEA and Enrico Vanin, CEO of Aon Italy, report that Aon’s digital transformation is based on regular and substantial involvement of the board, which demonstrates strong commitment and complete trust in the management, with a focus on medium and long-term sustainability. Johan Ekström, former head of customer proposition and marketing and a member of the Nordic management team at Skandia, reports that the Nordic subsidiary board includes three specialists in digital.

But even those boards that generally support digital may not embrace the scope of transformation required, or its urgency. Insurance companies are vulnerable to changes in the basis of competition brought on by disruptive forces within the industry, as well as external competition. A gulf exists between what businesses need and their understanding of the issues surrounding digital. “It has to start with the board,” says Amin. “You look at what trends are emerging, and then educate the board and take it from there.”

Solutions lie in educating the board and coaching them about the imperative of a business model with digital at its centre. Guglielmi recommends technical competency across the whole of the organisation, including at board level, with the board updated and engaged with digital topics twice a year.

At Aviva, Amin cultivates members of the board with genuine interest in digital. He increased engagement from senior leaders by inviting them to be judges in the hackathons. “We needed to help the organisation understand what was possible, show ideas and capabilities, and make believers out of non-believers.”

We needed to help the organisation understand what was possible, show ideas and capabilities, and make believers out of non-believers.

Nick Amin,

Group chief operations and IT officer, Aviva

Perhaps the biggest challenge for boards is overseeing a change in culture across the entire organisation. Culture has staying power: once it’s established, it can be hard to change, and this is particularly true in the insurance industry with its orientation towards safety, order and stability. If everyone believes that the way to be successful in the company is by avoiding risks and staying under the radar, a new strategy that prioritises risk-taking and innovation will face resistance unless the culture is addressed — and this means changing the way people think.

Achieving the desired cultural shift

The best kind of cultural patterns can encourage innovation, growth, market leadership, ethical behaviour and customer satisfaction. By contrast, an unhealthy or misaligned culture can impede strategic initiatives, erode business performance, diminish customer loyalty and discourage employee engagement.

The first step for any organisation seeking to bring about cultural change is to understand the gap between the current and desired culture — knowing where it wants to end up and then adjusting the hiring strategy accordingly, bearing in mind that poor culture fit is responsible for as many as 68 per cent of executive new hire failures.

A framework for thinking about culture

Having an integrated framework for assessing corporate culture and the personal styles of individuals makes it possible to apply insights about the culture to leadership and talent decisions.

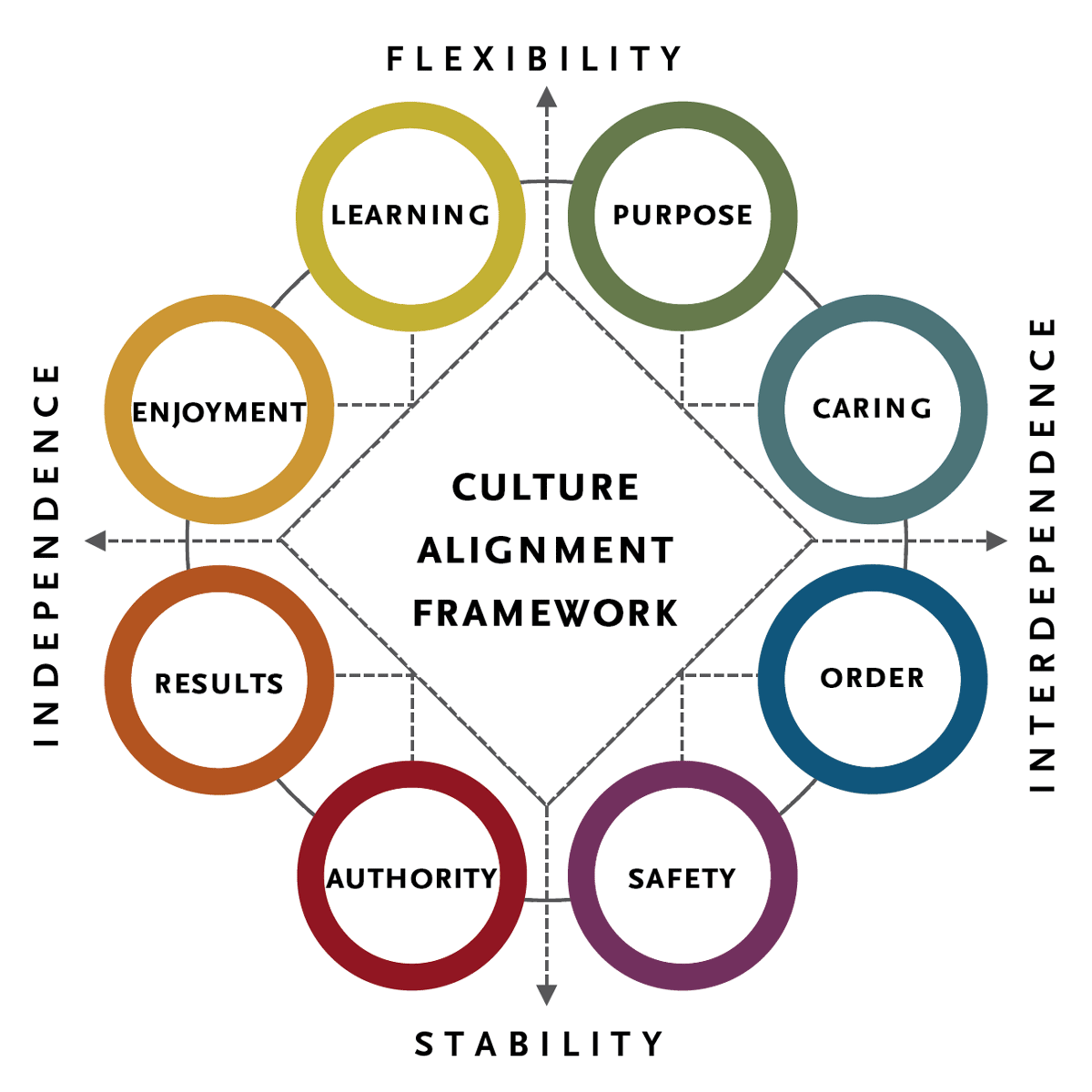

To fully understand an organisation’s culture, the most important dimensions to consider are the manner in which the organisation responds to change (i.e. is it oriented more towards stability or flexibility?) and whether it tends to think of its people as individuals or groups (i.e. is there a leaning towards independence or interdependence?).

Spencer Stuart has identified a set of distinct sociocultural styles or “basic assumptions,” which apply to both cultures and leaders. Together, these styles can be used to describe and diagnose highly complex and diverse behavioural patterns in a culture, which helps to understand how an individual executive is likely to align with and shape that culture (see diagram).

Safety, order and results tend to dominate in insurance companies; it can be very hard to bring about change when the primary focus is on stability. Insurance companies will need to place more emphasis on learning, purpose and caring — not just caring for employees but enabling them to provide an excellent service to customers at their moment of need. Specific behavioural shifts are necessary when moving to a more agile, innovative and networked culture, one in which it is acceptable to “fail small” in the quest to innovate — something that doesn’t come naturally in a sector that tends to be risk-averse.

A large part of the cultural challenge falls on the shoulders of senior leaders in insurance companies who need to change their own habits, just as they encourage behavioural change in others. It is one thing to devise new statements of purpose and values, but these need to be enacted from the top. If management does not change, then even the best attempts to innovate in a fluid, flexible and collaborative way will run aground.

4. Sluggish cultural transformation

Digital demands cross-functional collaboration, flattened hierarchies and the development of processes that make it easier to incorporate new ideas into the architecture in future. It is not something to be added onto a company, but a new way of imagining the business. Neil Brettell, who moved from Allianz to become chief commercial officer at MoneySuperMarket.com, points out that companies need to understand digital as a consumer-centric business model, rather than a means to become more cost efficient or marketing savvy.

For a more customer-centric model to succeed, a digital mindset must be embedded throughout the organisation; strategy, sales, marketing and operations must all be in alignment, if not fused. “There is no specific organisation dealing with the digital transformation,” says Peter Dahlgren, CEO of Nordnet and former head of the Life and Investment Management division for SEB. “The entire organisation is responsible for the shift.”

There is no specific organisation dealing with the digital transformation. The entire organisation is responsible for the shift.

Peter Dahlgren,

CEO, Nordnet

Insurance companies are moving from product-based businesses to being more customer-centric. In private insurance, companies are seeking ways of using data to make better and faster decisions, and providing touchpoints with customers on matters beyond premium payments and claims. In commercial insurance, they are partnering with their clients in order to manage risk, rather than providing a product that is active only during claims.

Change will come, but only if led from the top. Technological change puts new demands on leaders, who will need to ensure their organisations have the competence to analyse changing client behaviours and to make the most of the latest technology and service offerings. Learning and development plays an important role here, with some companies sending staff on tailored courses that cover organisational and cultural issues surrounding digital transformation. Not all learning comes from external sources: it is important to bring existing silos together, form cross-functional agile teams and increase the volume on the message that digitisation is a priority.

Guglielmi draws attention to the necessity of communicating effectively across geographies and technical competencies through the organisation. If initiatives are scattered it is difficult to achieve the critical mass of effort required for enterprise-wide transformation. “It takes time,” explains Amin. You have to educate thousands of people about digital. That’s what it takes, you have to say ‘this is digital, this is what it means to you, this is what it means to the business, this is what it means to the consumer, this is how we are all going to work together.’”

5. Talent bottlenecks

Like many insurers, Gianpeiro Zannier, marketing and consumer director at Reale Mutua, says his company is in an aggressive hiring mood, seeking digital savvy leaders with international profiles to drive the business forward. For many of the people they would like to target “insurance is not considered the favourite place to go,” he says. As a result, some companies struggle to fill every position they would like to. Patrick Bergander, CEO of RSA Scandinavia, says that the company works hard to attract digital talent from other industries, especially telecoms. Ekström reports that Skandia finds it hard to hire top digital talent from outside insurance, either to join Skandia or in a consulting capacity, although they have recruited a few high-calibre people from the banking industry.

Insurance is not considered the favourite place to go.

Gianpeiro Zannier,

Marketing and consumer director, Reale Mutua

Digital is a key driver to developing Aon’s affinity programmes — online platforms that manage the customer experience end-to-end. Their ongoing transformation has influenced their hiring strategies and Aon now consider talent from other industries, a broader mix of profiles, and those with experience in “connectivity to the client” and change management.

Aviva attracts data scientist and DevOps talent by running contests, hackathons, and graduate programmes in data science as well as IT and digital leadership. Amin built the company’s digital transformation organically, starting with the hackathons that now run globally, resulting in the appointment of the company’s chief digital officer, Andrew Brem. Unlike some, Aviva has no allegiance to industry-specific talent. “We decided as part of that process they would not come from the industry. We wanted somebody who had done it before, understood this whole new area and had a mindset that wasn’t legacy.”

Solutions to attracting the best talent in digital begin with creating a work environment and work method that rewards innovation and focuses on possibility, rather than incumbent processes. Amin explains, “It’s a different type of office, different type of furniture and a different working environment. People come with their laptops and sit down and work. You are there to develop X or Y or working on this particular initiative. An entire team works together to achieve an outcome.”

Companies might attract talent from insurtech start-ups or partner with successful digital companies. Pizzini makes the point that dozens of companies servicing the digital needs of insurance companies have emerged over the past several years. However, insurance companies are not taking advantage of the full range of digital opportunities made available by them. “Companies like ours serve the insurer with whatever they are comfortable with rather than asking the insurer to adapt to what we are able to provide. If the client says, ‘I want the data in this format, in this way’, because it’s data and because we are born in a different mentality, we say, ‘Okay. Just tell us what you want and we’ll give it to you.’”

Insurance for the future

Insurance companies are aware of the need to embrace digital technology but find it difficult to incorporate everything digital has to offer. Transformation takes place within the organisation and in interactions with customers and distributors. With evidence in other industries of winner-takes-all when it comes to digital transformation, insurance companies are keen to be on the front foot, but it is impossible to make all these changes all at once.

Older technology systems upon which companies currently depend are problematic to replace, requiring widespread adoption across a vast workplace. Leaders, already pushing for cross-functional collaboration and shifts in the corporate ecosystem, are having to find innovative ways to foster the technical side of transformation, as well as the business culture itself. Many are enlarging their notions of how insurance has been traditionally understood, partnering with customers to minimise risk, for example, or using technology to develop more personalised products. By failing to move on digital, insurers increase their risk of being disrupted from outside. While some insurance companies continue to rely on the barriers of entry that have protected them historically, leaders with an eye on the future will push towards new ways to generate value and seek the talent necessary to maintain their resilience and profitability in an increasingly digital age.